Investigación del accidente de Los Rodeos

27 Marzo 1977

On 27 March 1977 the collisión

of the 747s the at

Tenerife

REPORT

Special report

Publisher on December 2004 concerning the truth about this accident and the

responsible people.

GENERAL SECRETARY

PUBLICATIONS

English

Bibliography

TENERIFE

.

AVIATION DISASTER,

27.03.1977

Los

Rodeos

Airport

American

Airlines Pilot's Association (ALPA)

Air

Disasters: Dialogue from the Black Box

Stanley Stewart, 1986

Spanish:

“Subsecretaría Aviación Civil", Accident Report, 1978 ( ICAO CIRCULAR

AN-/56). Madrid.

*

* *

MOVIMIENTO POR

LA AUTODETERMINACIÓN Y

LA

INDEPENDENCIA DEL ARCHIPIÉLAGO CANARIO

M.P.A.IA.C.

NOTA: Se adjunta las declaraciones

del piloto jubilado de

la Cía. Española

IBERIA, responsable de la investigación del accidente de Los Rodeos en 1976, aparecidas

en el periódico de Tenerife, "El Día", en fecha del 9 de enero del

2005, Don JAIME VELARDE SILIO, actualmente retirado, donde

podrán comprobar que este profesional español no dice la verdad

sino que le echa toda la culpa al avión de

la KLM

, sin tener en cuenta que en su día

la ALPA

y la lectura de las cajas negras le echaba la culpa a la torre de control de

Los Rodeos en un porcentaje del 30 % y a los controladores. El gobierno

español tuvo que pagar el 30 % de las

indemnizaciones millonarias a las familias de los pasajeros por las

faltas cometidas por los controladores españoles,

llegando incluso a insinuar

la ALPA

, que el controlador de servicio estaba viendo un partido de fútbol en

la TV

mientras dirigía las operaciones y que empleaba una sola micro para los dos

aviones con una misma frecuencia y

que sus conocimientos del inglés eran muy malos.

Leer las reproducciones de las conversaciones de las

Cajas Negras y las consideraciones de

la ALPA

sobre el accidente y a quienes echan

la culpa y comparen con las declaraciones de D. Jaime Velarde y de toda

la prensa de la época, queriendo culpar a

nuestro Movimiento, el cual no tuvo nada que ver con este accidente

ni de cerca ni de lejos, ni directa ni indirectamente, incluso con

el incidente del aeropuerto de Gando en Las Palmas, del cual se nos quiso

acusar, sin que nunca hallaran a los supuestos responsables.

*

* *

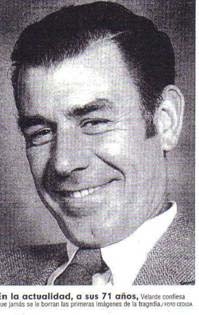

Jaime

Velarde Silió:

PILOTO

JUBILADO DE IBERIA Y RESPONSABLE DE

LA INVESTIGACIÓN DEL

ACCIDENTE AÉREO DE LOS RODEOS

"En

los accidentes aéreos no hay culpables,

sí

responsables"

CLAUDIO

ANDRADA, S/C. Tfe, 9 enero 2005

Aunque lo pareciera, el domingo del día 27 de marzo de 1977 no terminaría

para Juan Velarde como otro día festivo cualquiera. A las 17:06 horas GMT,

momento en que disfrutaba con su familia en las afueras de Madrid de su merecido

descanso, este piloto de Iberia (en la actualidad de 71 años y jubilado, aunque

sigue volando aparatos de época junto a su hijo, de idéntica profesión) no

podía imaginar que a la llegada a su domicilio un mensaje reclamaba su

presencia porque se había producido el que hasta la actualidad (da gracias a

Dios de que así sea) ha sido el accidente aéreo con mayor número de víctimas

mortales: el registrado en Los Rodeos, en el que perecieron 583 personas por la

colisión de dos Boeing 747, uno de la compañía holandesa KLM y otro de la

americana Pan Am.

Aunque lo pareciera, el domingo del día 27 de marzo de 1977 no terminaría

para Juan Velarde como otro día festivo cualquiera. A las 17:06 horas GMT,

momento en que disfrutaba con su familia en las afueras de Madrid de su merecido

descanso, este piloto de Iberia (en la actualidad de 71 años y jubilado, aunque

sigue volando aparatos de época junto a su hijo, de idéntica profesión) no

podía imaginar que a la llegada a su domicilio un mensaje reclamaba su

presencia porque se había producido el que hasta la actualidad (da gracias a

Dios de que así sea) ha sido el accidente aéreo con mayor número de víctimas

mortales: el registrado en Los Rodeos, en el que perecieron 583 personas por la

colisión de dos Boeing 747, uno de la compañía holandesa KLM y otro de la

americana Pan Am.

Precisamente

porque mañana, lunes, Nat Geographic, de Digital + ofrece a las 14:00, 19:00 y

23:00 horas un reportaje alusivo a la tragedia, EL DÍA logró

entrevistar a este piloto de Iberia que conoce de primera mano qué sucedió y cómo

se vivieron los momentos posteriores al terrible accidente aéreo. No en vano

fue comisionado para que se encargara de la investigación oficial por parte de

la asociación de pilotos que existía en aquella época.

-¿Por

qué lo llamaron a usted para hacerse cargo de la investigación?

-Estaba

especializado por cuenta de la asociación de pilotos españoles en la

investigación de accidentes aéreos, ya que había realizado un curso en la

universidad del Sur de California, aunque en realidad mi mayor y primera

experiencia fue precisamente ésta. No tuve mucha suerte.

-Y

con el aeropuerto de Los Rodeos cerrado, ¿cómo llegó a Tenerife?

-La

asociación me dijo que me buscara la manera de llegar, y yo sabía que el

tiempo corría en contra, ya que la propia actuación de los servicios de

emergencia podían borrar pistas clave. Salí esa misma noche en un Iberia que

iba a Caracas, vía Gran Canaria, y el único medio que existía era un helicóptero.

Dio la casualidad que conocía al piloto y le rogué que me desplazara a

Tenerife. Me fui como teórico mecánico de vuelo y me puse el mono. Llegué a

las 5 de la mañana, aún sin amanecer, con niebla cerrada, y aún quedaban

rescoldos, sobretodo de la avión de

la KLM

y me puse manos a la obra.

-¿Qué

fue lo que más lo impresionó al presenciar lo que se le venía encima?

-Era

espeluznante. Se percibía la tragedia por la tristeza en los rostros de la

gente y un olor ocre que impresionaba enormemente. Y sin darle coba a los

tinerfeños, tengo que decir que la respuesta solidaria fue de tal magnitud que

hubo que emitir un bando por la radio para rogar que dejaran de donar sangre

porque la cantidad era tal que colapsaba las entradas al recinto portuario.

Impresionante.

-¿Cuáles

fueron los primeros pasos en la investigación?

-Eso

lo tenía muy claro. Croquis, fotografías, dibujos de los restos principales...

lo antes posible, y lo segundo, afrontar la situación y responder a lo que

recomienda la asociación internacional de pilotos para ponerme a disposición

de la tripulación afectada, que estaba en el hospital.

-¿Hubo

cortapisas para la investigación o presiones?

-La

situación en España era dificilísima, ya que la estructura pertenecía al ejército

del Aire, de hecho me llamó el general Franco Iribarne Garai y fue muy

valiente, porque mandó la investigación a EEUU, donde se llevó a cabo. Le

mostré mi disponibilidad y se buscó la verdad. Todo un orgullo.

-¿Y

hacia dónde fue la culpa?

-En

un accidente aéreo no hay una sola causa y no hay culpables, sino un cúmulo de

causas y responsables. Lo cierto es que hubo una responsabilidad del piloto de

la holandesa KLM, una de las compañías más prestigiosas y pionera de Europa.

-La

realidad es que a España no le cayó nada...

-Sí,

pero en la búsqueda de la verdad, tras dos años de investigaciones, las

presiones de Holanda fueron muchas. Pero lo que nos preocupaba era llegar a qué

fue lo que pasó, y la responsabilidad llegó a señalar sin lugar a dudas al

piloto de

la KLM.

-¿Cuándo

se supo que la responsabilidad no era española?

-Aunque

siguieron las investigaciones dos años más en EEUU, nosotros, no como

investigadores sino como españoles, tras oír las "cajas negras" con

las conversaciones de las dos naves y los controladores supimos que la

responsabilidad fue del piloto de KLM.

LA CLAVE

"Buscamos

siempre la verdad"

Cuando

se presentaron las primeras conclusiones, una vez oídas las "cajas

negras" de los dos aparatos siniestrados, Velarde confiesa que "la

parte holandesa, precisamente de una de las compañías más antiguas y

prestigiosas de Europa, trataron de hallar alguna responsabilidad en la

comunicación de los controladores que operaban en aquel momento en el

aeropuerto de Los Rodeos, pero -añade- la labor de los mismos fue impecable,

incluso por encima del nivel, ya que el aluvión de tráfico que les llegó de

repente, merced al cierre por un atentado del MPAIAC del aeropuerto de Gando,

fue impresionante". Apostilla Jaime Velarde que buscaban la verdad como única

opción y b "estaba dispuesto a fijar responsabilidades donde las hubiera,

incluso en contra de los intereses de España si así hubiera sido, aunque después

pudieran machacarme (sonríe), pero la realidad es que la responsabilidad fue un

fallo clamoroso del piloto de la compañía KLM, que no esperó la autorización

de la torre y puso los motores a tope para despegar, y pasó lo que pasó; pero

también había niebla, y hubo un leve corte en las comunicaciones... La cierto

es que cuando sucede un accidente así nunca se produce por una sola causa, sino

por una suerte de infortunios", aclara el veterano piloto.

Publicado

en el periódico El

Día, 9 enero 2005

*

* *

English

Bibligraphy

TENERIFE

. AVIATION DISASTER, 27.03.1977

Los

Rodeos

Airport.

American Airlines Pilot's Association (ALPA)

Air Disasters: Dialogue from the Black Box

Stanley

Stewart, 1986

Spanish Subsecretaría Aviación Civil", Accident Report,1978

(ICAO CIRCULAR AN-/56).

Madrid.

*

* *

Abbreviations

and Glossary

AINS

Area Inertial Navigation System

ASR

Área Surveillance Radar

ATC

Air

Traffic Control

BEA

British European Airways

CVR

Cockpit Voice Rccorder

FDR

Flight Data Recorder

F/E

Flight Engineer

FIR

Flight Information Region

F/O

First Officer

GMT

Greenwich Mean Time

HF

High Frequency

IFR

Instrument Flight Rules

IMC

Instrument Meteorológical Conditions

INS

Inertial Navigation

System

KLM

Koniges Lucht Macht — Royal Dutch Airlines

kt

knots

local

Local time if different to GMT

MHz

Megahertz

NDB

Non-Directional Beacon

nm

nautical mile

Phonetic

Alphabet used for clear and distinct spelling. This is also used as a

Alphabet

shorthand when referring to aircraft, so G-ARPI becomes ¨Papa

India

'

QNH

Mean Sea Level Altimeter Pressure Setting

R/T

Radio Telephony

rpm

revolutions per minute

S/O

Second Officer

Tel.

Telephone

V1

Decision speed - the go or no-go decision point on take-off

V2

Mínimum safe speed required in the air after an engine failure at VI

VFR

Visual Flight Rules

VHF

Very High Frequency

VMC

Visual Meteorological Conditions

VOR

VHF Omnidirectional range Radar beacon

*

* *

Pan American Flight

PA1736, a Boeing 747 — registration N736PA — on charter

to Royal Cruise Lines, departed Los Angeles on the evening of 26 March local

date (01.29hrs GMT, 27 March) with 275 passengers for New York and Las Palmas.

On the stop-over at JFK a further 103 passengers boarded, bringing

the total to 378. The crew of 16 was changed. At 07.42hrs (all

times GMT) Flight PA1736, call sign Clipper 1736, departed Kennedy for Las

Palmas under the command of Captain Víctor Grubbs, with First Officer (F/O)

Robert Bragg and Flight Engineer (F/E) George Warns. Tending the passengers'

needs were 13 flight attendants. About 1 1/4 hours after the Clipper's

take-off from

New York

, KLM Flight KL4805 departed from

Amsterdam

at 09.00hrs also en route to

Las Palmas

. The KLM Boeing 747, registration PH-BUF,

was operated by the Dutch airline on behalf of Holland Internation travel

group, and on board were 234 tourists bound for a vacation in the

Canary Islands

, plus one travel guide. After

disembarking the passengers, PH-BUF was scheduled as Flight KL4806 to fly back

to

Amsterdam

with an equally large group of returning holidaymakers. The Dutch crew

rostered for the round trip was commanded by Captain Jacob van Zanten,

a senior KLM training captain, and

with him on

the flight deck were F/O Klass Meurs and F/E William Schreuder. There

were 11 cabin staff to look after the charter

passengers.

As

both Boeing 747s converged on

Las Palmas

, the bomb was detonated in the terminal building about one hour before KLM's arrival.

With closure of the airport Flight KL4805 simply diverted to Los Rodeos on

Tenerife

pending the reopening of the airport, and

landed at 13.38hrs GMT, the same time as local. At first Captain van

Zanten was reluctant to disembark his passengers in case

Las Palmas

suddenly opened, but after 20 min of

waiting he reversed his decision and buses arrived to transport the

travellers to the terminal. Pan Am's arrival from

New York

was also affected, but since the opening of

Las Palmas

seemed imminent and they had adequate fuel,

Captain Grubbs asked to hold at altitude near

Tenerife

. The request was refused and Flight PA1736 also landed at Los Rodeos

at 14.15hrs, about 30min behind KLM. The weather was clear and sunny. Many

aircraft were diverted from

Las Palmas

that day and, with

Tenerife

's own week-end traffic, Los Rodeos was becoming overcrowded. To make use of all

available space, aircraft were parked on the

runway 12 holding area situated only a short distance from the

main apron on the northern side of the runway. KLM was

parked nearest the threshold of runway 12 followed in sequence by a Boeing

737, a

Boeing

727, a

DC-8 and the Pan Am Boeing 747 taking up the rear. These aircraft filled

the holding area and subsequent arrivals were parked where space could be found

on the main apron. Airport staff worked overtime to handle the doubled amount of traffic.

Meanwhile,

the Dutch crew, concerned that there might be insufficient time for them

to complete the round trip

back to

Holland

; contactad

Amsterdam

on high frequency long range radio. A few years before, a Dutch captain was

able to extend the crew's duty day at his own discretion according to a number

of factors which could be readily assessed on the flight deck. The

situation was now infinitely more complex

and crews were advised to liaise with

Amsterdam

in order to establish

a limit

to their duty

day. Captains were bound by this

limit and

could be prosecuted under the law

for exceeding their duty time.

Amsterdam

replied that if the KLM flight could depart

Las Palmas

by 19.00hrs at the latest they would not exceed their

flight time limitation. This would be confirmed by a message in writing in

Las Palmas

.

Shortly

after Pan Am's arrival,

Las Palmas

was declared open at about 14.30hrs and

aircraft began to depart for

Grand Canary

Island

. Since the Clipper charter flight's

passengers were still on board they were prepared for a quick departure. Two

company employees joined the flight in Tenerife for the short hop to

Las Palmas

and were placed in the jump seats on the

flight deck, bringing the total on board to 396; 380 passengers and 16

crew. As the aircraft on the holding area positioned between the two 747s were

permitted to depart, Pan Am called for clearance in turn. When start-up was

requested the controller explained that although there was no air traffic delay

they might have to wait. Taxying via the parallel

taxi route past the main apron was not possible because of overcrowding, and

the holding area exit on to the runway was probably blocked by KLM. The other

aircraft parked on the holding area, being smaller in size, had managed to pass

behind the KLM 747 on their departure for

Las Palmas

. Unable to follow suit, N736PA was trapped until the Dutch aircraft moved.

The KLM passengers were

summoned from the terminal building, but it took time to bus them back to the

aircraft and reboard the flight. Of those who landed in

Tenerife

only the Dutch company travel guide remained behind, giving a total on

board of 248; 234 passengers and 14 crew. In the meantime, many aircraft were arriving

at the reopened

Las Palmas

Airport

and it, too, was becoming congested. Los

Rodeos was co-ordinating the situation with

Las Palmas

personnel and soon news carne through of a further delay for the Dutch

flight. As yet no gate was available for KLM

and Captain van Zanten had no choice but to wait. The Dutch crew

maintained cióse contact with

Tenerife

tower over their departure time and expressed

concern over the delay. They had now been on the ground for over two hours.

It was unlikely a speedy turn-round could be expected in

Las Palmas

owing to the congestión, so to ease the situation the Dutch captain

made the somewhat late decisión to refuel at

Tenerife

. Since they were still awaiting departure clearance

owing to the unavailability of the gate at

Las Palmas

it would save time on the transit to refuel there for the return

Tenerife-Las Palmas-Amsterdam journey. The fuelling process, however, would take

about 30min. The Pan Am crew, still hemmed in on both sides, was far from happy

with this decision. N736PA was free to leave

at any time but could not do so until KLM moved. The American

first officer and flight engineer walked out on to the tarmac to measure the

distance behind KLM but confirmed that there was insufficient space. Captain Grubbs

had been listening in on KLM's radio conversation with the tower and knew of the

Dutch captain's desire to leave as early as possible but, unaware of KLM's tight

schedule, he felt the Dutch were further delaying both their departures

unnecessarily. Clearance for Captain van Zánten to start could come through at

any moment but would now have to wait completion of KLM's refuelling. To complícate

matters the weather was beginning to deteriórate. Los Rodeos airport is

situated at an elevation of 2,000ft in a kind of hollow between mountains and is

frequently subject to the presence of low-lying cloud, reducing visibility. In

fog, the moisture content and therefore visibility remains relatively constant,

but with low cloud drifting across an airport the visibility can change rapidly from several kilometres to zero in a matter of minutes. There was

a danger of the weather closing in and preventing departures for a long

period. Clouds of varying density from light to dark were blowing down the

departure runway 30 with the northwesterly 12

to 15kt wind. At times* the runway visibility increased to two or three

kilometres and at other times dropped to 300m. The runway centre line

lights were inoperaíive making judgement on take-off more difficult. There was

also heavy moisture in the air with

the passage

of the clouds, and aircraft were frequently

required to use their windscreen wipers to clear the view when taxying.

The time was now about

16.30hrs and the Pan Am crew had been on duty for 103/4

hours. They were beginning to feel the strain and were looking forward to their

rest after the short 25min hop to

Las Palmas

. The KLM crew had been on duty for 8% hours, but they still had to complete the

round trip back to

Amsterdam

. Three hours remained to the deadline for departure out of

Las Palmas

, but with the weather worsening this time limit

could easily be compromised

if they had to wait for the clouds to clear. As it was, the duty limit had not

yet been confirmed, and even with fuel on board the transit through

Las Palmas

could be slow in the overcrowded airport.

If the crew ran out of hours and PH-BUF got stuck in

Las Palmas

, there would be more than a few problems for the

ground staff. To begin with, it would be almost impossible to find 250 beds at such

short notice and the joining passengers would probably have to spend the night

in the airport. The crew would also be late back to

Amsterdam

and the aircraft would miss the next day's schedules. It was hardly surprising

that the Dutch crew were keen to get away. The Americans, too, a little

irritated at being held

back by KLM, would also be happy to leave Los Rodeos behind.

Permission

for KLM to depart did not come through

until refuelling was almost finished

and vindicated Captain van Zanten's decision to complete the process in

Tenerife

. As the Clipper crew waited, the American passengers were invited to view the

flight deck, and questions about the flight were answered. At 16.45hrs Captain

van Zanten signed the fuel log and at 16.51hrs, with pre-start checks completed,

KLM requested start-up. Alert to the situation Pan Am heard KLM's radio

call.

'Aha', said Captain

Grubbs, 'he's ready!'

The

Clipper also received start clearance as KLM was starting engines and the two crews prepared to taxi.

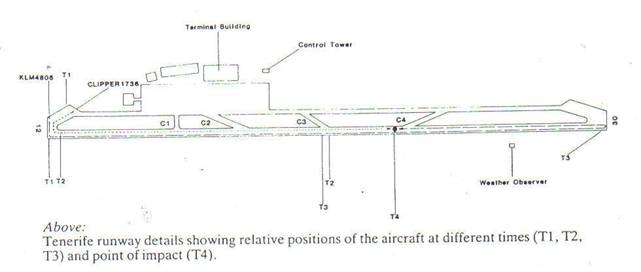

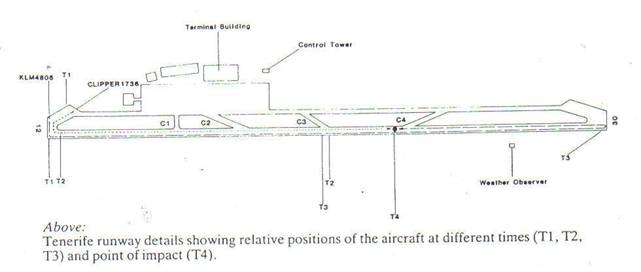

Owing to the prevailing northwesterly wind, both aircraft

had to enter the runway from the holding area for runway 12 and taxi right to

the far end of the ll,150ft (3,400m)

runway, a distance of over two miles, for take-off in the opposite direction on runway 30.

At that time the control

tower had three radio frequencies available of 121.7MHz, 118.7MHz and 119.7MHz.

Only two controllers were on duty, however,

and 118.7MHz was used for ground taxi instruction and 119.7MHz, the approach

frequency, for both take-off and approach communication. KLM was cleared to taxi

at 16.56hrs but was instructed to hold short of the runway 12 threshold

and to contact approach on 119.7MHz. On establishing contact, Flight KL4805

requested permission to enter and back-track on runway 12. Clearance was

received to taxi back down the runway and to exit at the third turn-off, then to

continue on the parallel taxiway to the runway 30 threshold. The first officer

mis-heard and read back 'first exit',

but almost immediately the controller amended

the taxi instruction. KLM was directed to back-track the runway all the way,

then to complete a 180° turn at the end and face into the take-off direction. The

first officer acknowledged the instruction but the Captain, now concentrating on

more pressing matters, was beginning to overlook radio call. The visibility was

changing rapidly from good to very poor as they taxied along the runway and it

was proving difficult to ascertain position. The approach controller issuing

taxi instructions could see nothing from the control tower so was unable

to offer any help. One minute later the KLM Captain radioed the approach

controller asking if they were to leave the runway at taxiway Charlie 1. Once

more KLM were instructed to continue

straight down the runway.

Pan Am received taxi

instructions on the ground frequency of 118.7MHz and was also directed to hold

at the 12 threshold. Captain Grubbs was happy to wait until after KLM's

departure but almost immediately they were cleared to follow the

Dutch flight. The instruction was given to back-track on the runway and leave by

the third exit but because of the ground controller's heavy Spanish accent the

crew had a great deal of trouble understanding the clearance. With better Communications the Captain might well

have established his preference to hold position, but since several attempts

were required to comprehend a simple direction it was obviously going to be

easier to comply with the controller's wishes.

Pan Am was given instructions to back-track on the ground frequency so the

Dutch crew, already changed to approach, were at first unaware that the Americans

were following behind. As Flight PA1736 began its journey down the runway,

ground cleared Captain Grubbs to contact approach. At 17.02hrs KLM now

heard the Pan Am crew call approach control and request confirmation of the

back-track instruction.

'Affirmative', replied

approach, 'taxi into

the runway and leave the runway third, third

to your left, third'.

By

now the Americans had been on duty for over 11 1/4 hours and were feeling

tired.

The Dutch crew had been on duty for over 9 1/4 hours, of which about 3 1/4 hours

had been spent waiting on the ground at

Tenerife

. The visibility began to drop

markedly and fell to as low as l00m in the path of the two Boeing 747s taxying down the runway. It was difficult to spot the exits. Thick cloud

patches at other parts on the airport reduced visibility right down to zero.

All guidance was given via the radio as no one could see anyone else and

Los Rodeos was not equipped with expensive ground radar. Captain van Zanten,

when approaching taxiway Charlie 4, again

asked his co-pilot if this was

their turn

off, but the first officer repeated that the instruction had been given

to back-track all the way to the end.

The KLM crew had switched on the wipers to clear the moisture and suddenly, through the mist, could see some lights.

The first officer confirmed the sighting.

'Here comes the end

of the runway.'

'A couple of lights to

go', replied the Captain. Approach then called asking Flight

4805 to state its position.

17.02:50, Approach

R/T: 'KLM 4805, how many taxiway did you pass?'

17.02:56, KLM 4805 R/T: 'I think we just

passed Charlie 4 now.'

17.03:01, Approach R/T: 'OK. At the end of the runway make a

180 and report ready for ATC (Air Traffic

Control) clearance.'

The KLM crew now asked if

the centre line lights were operating and the controller replied he would check.

The Americans were still not sure of

the correct turn-off because of the language difficulties and once again asked

for confirmation that they were to exit the

runway at the third exit.

17.03:36, Approach

R/T: 'Third one sir, one, two, three, third, third one.'

17.03:39, PA1736 R/T: 'Very good, thank you.'

Approach

R/T:

'Clipper 1736, report leaving the runway'.

The Clipper replied

with his call

sign. As the Americans continued down the runway the taxi check was commenced.

Instruments and flying controls were checked, the stabiliser was set and the

flaps were positioned for take-off, etc. Meanwhile, the Pan Am crew were also

trying to spot the turn-offs from the runway in order to count along to the

third one, but were having a great deal of trouble in seeing properly. They

passed and recognised the 90° taxi exit but were unable to see the taxiway

markers so were unsure how many turn-offs they had passed. The allocated exit

involved following a 'Z' shaped pattern to manoeuvre on to the parallel taxiway

and was going to be difficult for the large Boeing 747 to negotiate. Finding

Charlie 3 was also proving to be difficult since its shape was similar

to Charlie 2.

As

KLM approached the end of the runway

the controller called both aircraft regarding

the centre line lights.

Approach

R/T: '-For your information, the centre line lighting is

out of service.'

Each flight

acknowledged in turn and checked the minimum visibility

required for take-off in such

circumstances. By now KLM was commencing the turn at the end of the runway and

much was on the Captain's mind. Turning a large aircraft through

180° on a narrow

runway requires a degree of

concentration and temporarily distracted the captain from other duties. The time

was now almost 17.05hrs and

the restriction

for departure out of

Las Palmas

was

rapidly approaching. If they didn't

depart soon they could easily miss it. By good fortune the visibility

had improved sufficiently for take-off and with a reduction in moisture

the wipers were switched off. If they could get away quickly in the gap in the

weather everything should be fine. As the take-off approached, the captain,

having to concentrate on so many Ítems, ¨seemed a little absent from all that

was heard on the flight deck'. He called for

the check list.

KLM F/O: 'Cabin warned. Flaps set ten, ten.'

KLM

F/E: 'Eight

greens.'

KLMF/O: 'Ignition.'

KLM F/E: 'Is coming — all on flight start.'

KLMF/O:'Body

gear.'

KLM F/E: 'Body gear OK?'

The turn was now almost complete

with the aircraft lining

up on runway 30. KLM Capt: 'Yes, go ahead

.'

The visibility now improved to

900m, but a cloud could be seen ahead moving down the runway. There was just enough time to get away. The Pan Am

aircraft was approaching exit

Charlie 3 at this

stage, half way along the 3,400m runway, but

in the bad conditions was unobserved by KLM. Nothing could be seen of the

locations of the 747s from the tower. The two aircraft faced each other unseen

in the mist.

KLM F/O: 'Wipers on?'

KLM Capt: 'Lights are on.'

KLM F/O: 'No ... the wipers?'

KLM Capt: 'No I'll

wait a bit...

if I need them I¨ll ask.'

KLM F/O: 'Body gear disarmed, landing lights on,

check list completed.'

At 17.05:28 the captain stopped the

aircraft'at the end of the runway

and immediately opened up the

throttles.

KLM F/O: 'Wait a minute,

we don't have an ATC clearance.'

The KLM captain, being

a senior training pilot,

had a lack of recent route practice and was

more used to operations in the simulator

where he spent a great deal

of his time.

In the simulator radio work

is kept to a minimum on the grounds of

expediency in order to concentrate on drills

and procedures, and

take-offs are often conducted without

any formalities. Such an oversight, although alarming, can perhaps be explained

by the circumstances. On closing the throttles the captain replied, 'No, I know that,

go ahead, ask'. The first officer pressed the button

and asked for both the take-off clearance and the

air traffic

clearances in the same transmission.

KLM F/O R/T: 'KLM4805 is now ready for take-off and we are waiting for our ATC

clearance.'

Pan Am arrived at exit Charlie 3 just

as approach began to read back KLM's ATC

clearance. Having miscounted the

turn-offs, they missed their

designated taxi route and continued

on down the runway unaware of their

mistake. They were still about

l,500m from the threshold and out of sight of KLM. It was now over

two minutes since the approach controller's

last call to Pan Am requesting him

to report leaving the runway, and in the KLM

crew's desire to depart, the fact that

Pan Am was still in front of them, not having cleared the runway, was being overlooked.

17.05:53

Approach R/T: 'KLM4805, you are cleared to the papa beacon, climb

to and maintain flight level nine zero. Right turn after take-off,

proceed with heading zero four zero until intercepting the three three five

radial from Las Palmas VOR [VHF omnidirectional range radio beacon].'

Towards the end of this transmission, and before the controller had finished

speaking, the KLM captain accepted this as an unequivocal

clearance to take-off and said, 'Yes'. He opened up the thrust levers slightly

with the aircraft held on the brakes and •*"

paused till the engines stabilised.

17.06:09 KLM F/O R/T: 'Ah, roger sir, we're cleared to

the papa beacon, flight level nine

zero…’

As the

first officer spoke the captain released the brakes at 17.06:11 and, one second later, said,

'Let's go, check thrust'. The

throttles were

opened to take-off power and the

engines were heard to spin

up. The commencement of the take-off in

the middle of reading back the clearance caught the first officer off balance

and during the moments which followed this, he 'became noticeably

hurried and less clear'.

KLM F/O R/T: '. . . right turn out, zero

four zero, until

intercepting the three

two five. We are now at take-off.'

The last sentence

was far from distinct. Did he say 'We are now uh, takin'

off? Whatever was said the rapid

statement was sufficiently ambiguous to cause concern and both the approach

controller and the Pan Am first

officer replied imultaneously.

17.06;18

Approach R/T: ‘OK…’

In

the one-second gap in the controllers' transmission,

Pan Am called

to make their position clear. The two spoke

over the top of each other.

17.06;19

Approach R/T: '…stand-by for take-off, I will call you.'

Pan

Am F/O R/T: 'No, uh . . . and we are still

taxying down the runway, the Clipper 1736.'

The combined transmissions

were heard as a loud three-second squeal on the KLM flight deck causing

distortion to the messages. Had the words been clearer the KLM crew might have

realised their predicament but, only moments later, a second chance carne for

them to assess the danger. The controller had received only the Clipper call

sign with any clarity but immediately called back in acknowledgement.

17.06:20 Approach R/T: 'Roger, papa alpha 1736, report the runway

clear.'

On this one and only radio call the

controller, for no apparent reason, used the call

sign papa alpha instead of Clipper.

17.06:30 Clipper

R/T: 'OK we'll report when we're clear.'

Approach R/T: Thank you.'

In spite of these

transmissions the KLM Boeing 747 continued to accelerate down

the runway. The words were lost to the pilots concentrating on the take-off but

they caught the flight engineer's attention. He tentatively inquired of the situation.

KLM F/E: Is he not clear,

then?'

KLM Capí: 'What did

you say?'

KLM F/E: 'Is he not clear, that Pan American?'

KLM Capí: 'Oh, yes.'

The co-pilot also answered

simultaneously in the affirmative and the flight engineer

did not press the matter. The KLM aircraft continued on its take-off run into

the path of Pan Am.

It is difficult for most

people to understand how anyone as experienced as the Dutch captain could have

made an error of such magnitude. For those used to regular

hours and familiar surroundings, with nights asleep in their own time zone ''and

frequent rest periods, it may be impossible to comprehend. But the flying

environment, although for the most part routine, can place great strain on an

individual. Constant travelling in alien environments, long duty days, flights

through the night and irregular rest patterns can all take their toll. The Dutch

crew had been on duty for almost 9!/2 hours and still had to face the

problems of the transit in

Las Palmas

and the return to

Amsterdam

. Lack of recent route experience for the

captain, especially in these trying conditions, did not help. The pressure

was on to leave Los Rodeos as early as possible and the weather was not making

it any easier. A gap in the drifting cloud had presented itself

and the captain had taken the opportunity to depart. Close concentration was

required on the take-off as clouds were once again reducing visibility. At such

moments the thought process of the brain can reach saturation point and can

become overloaded. The 'filtering effect' takes over and all but urgent

messages, or only important details of the task in hand, are screened from the

mind. Radio Communications, which were being

conducted by the first officer, were obviously placed

in a low priority in the minds of both the pilots once the take-off had been commenced.

The controller's use of papa alpha instead of Clipper — the only occasion

that day on which this identification was used — reduced the chances of registering

the transmission.

On the Clipper

flight deck the crew were sufficiently alarmed by the ambiguity of the

situation to comment although they were not as yet aware that the KLM had started his take-off run.

Pan Am Capt: 'Let's get the hell out of here.'

Pan Am F/O: 'Yeh, he's anxious, isn't

he.'

Pan Am F/E: 'Yeh, after he held us up for an hour and a half . . . now he's in a

rush.'

The

flight engineer had no sooner finished speaking when the American captain saw

KLM's landing lights appear, coming straight at them through the cloud bank.

Pan Am Capt: 'There he is . . . look at him . . . that .

. . that son-of-a-bitch is coming.'

Pan Am F/O: 'Get off! Get off! Get off!'

Captain Grubbs

threw the aircraft to the left and opened up the throttles in an attempt to run

clear. At about the same time the Dutch first officer, still unaware of

Pan Am's presence, called 'Ve one', the

go or no-go decisión speed. Four seconds

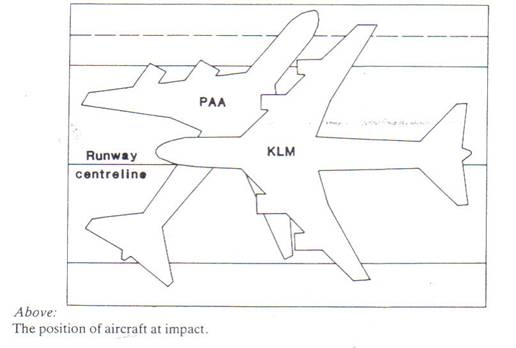

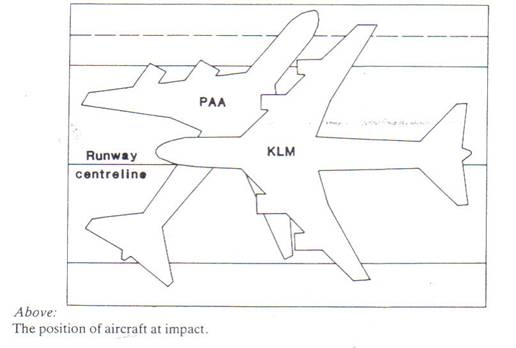

later the Dutch crew spotted the Pan Am 747 trying to scramble clear.

KLM Capt:'Oh…..’

The

Dutch captain pulled back hard on the

control column in an early attempt to

get airborne. The tail struck the ground in the high nose up angle leaving a 20m

long streak of metal on the runway surface. In spite

of the endeavours of both crews to take avoiding action, however, the collision

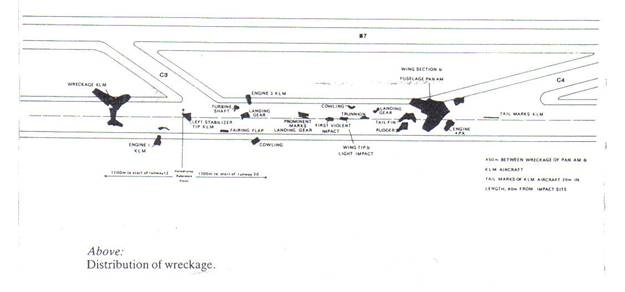

was inevitable. The KLM 747 managed to become completely airborne about l,300m

down the runway, near the Charlie 4

turn-off, but almost immediately slammed into the side of Pan Am. The

nosewheel of the Dutch aircraft lifted

over the top of Pan Am and the KLM number one engine, on the extreme left, just

grazed the side of the American aircraft. The fuselage of the

KLM flight skidded over the top of the other but its main landing gear srnashed into

Pan Am about the position of Clipper's number three engine. The collision was

not excessively violent and many passengers thought a small bomb had exploded.

Pan Am's first class upstairs lounge

disappeared on impact, as did most of the top of the fuselage, and the

tail section broke off. Openings appeared on the left side of the fuselage and some

passengers were able to escape by these routes. The Pan Am aircraft had its nose

sticking off the edge of the runway and survivors simply jumped down on to the

grass. The first class lounge floor had collapsed, but the flight crew, plus the

two employees in the jump seats, managed to leap below into what was left

of the first class section and make their escape. On the left side the

engines were still turning and there was a

fire under the wing with explosions taking place.

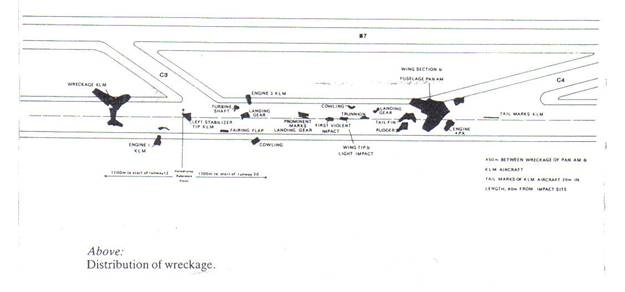

The

main landing gear of the KLM flight sheared off on impact and the aircraft sank

back on to the runway about 150m further on. It skidded for another 300m and

as it did so the aircraft slid to the right, rotating clockwise through a

90-degree turn before coming to a halt. Immediately an extensive and

violent fire erupted engulfing the wreckage.

The

controllers in the tower heard the explosions and at first thought a fuel tank

had been blown up by an .error, but soon reports of a fire on the airport began to

be received. The fire services were alerted and news of the emergency was

transmitted to all aircraft. Both 747s on the runway were called in turn without

success. The fire trucks had difficulty

making their way

to the scene of the fire in the misty and congested airport, but

eventually the firemen saw the flames through the fog. On closer inspection the

KLM aircraft was found completely ablaze. As they tackled the conflagration

another fire was seen further down the runway, assumed to be a part of the same

aircraft, and the fire trucks were divided.

It was then discovered that a second aircraft was involved and, since the KLM

flight was already totally irrecoverable, all efforts, for the moment, were

concentrated on the Pan Am machine. Airport staff and individuals who happened

to be on the premises bravely ran to help the survivors.

When

the extent of the disaster became known a full emergency was declared on the island and ambulances and fire fighting teams were summoned from

other towns. Local radio broadcast requests for qualified personnel to offer

their services. Although the request for help was made with the best of

intentions the rush to the airport soon caused a traffic jam, but fortunately

not before the survivors were dispatched to hospital. Large numbers of islanders

also kindly donated blood.

Of

the 396 passengers and crew aboard the Pan Am flight only 70 escaped from the wreckage and nine

died later

in hospital.

335 were killed. All 248 aboard the KLM

aircraft perished. On that Sunday evening of 27 March 1977, 583 people lost their

lives, and as if to mock those in fear of flying, the accident happened on the ground.

It stands on record as the world's worst disaster in aviation history.

As the survivors were

being tended in

Santa Cruz

, firemen at the airport continued to fight the infernos on the runway. In the

end, in spite of the intense blaze, the

firefighters managed to save the left side of the Pan Am aircraft and the wing,

from which 15,000-20,000kg of fuel were later recovered. It was not until the

afternoon of the following day that

both fires were completely extinguished.

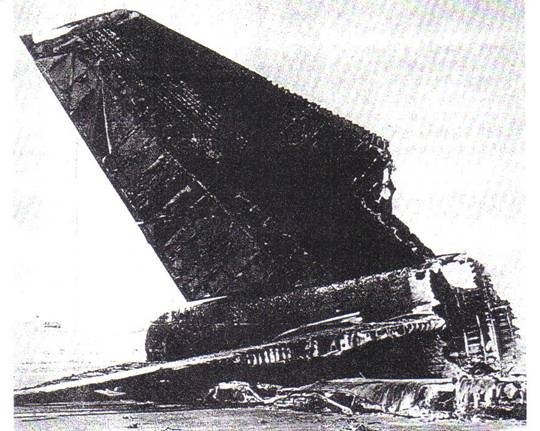

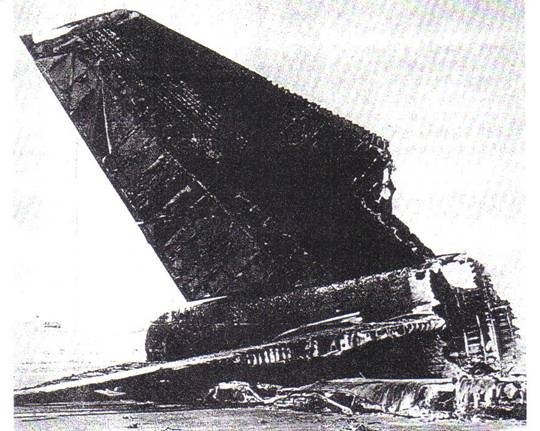

Below:

The burnt out tail of the KLM 747 at Los Rédeos airport.

Associated Press

The

events leading to this tragic accident are, summarized in the

report of the International Commitee set up to

investígate the causes of the accident on behalf of the Insurances Companies,

and Spanish " Subsecretaría de Aviación Civil

", Accident Report, 1978 ( ICAO circular 153-AN/56

), and the American Airline Pilot's Association (ALPA) Accident Report, 1978.

On 27 March 1977 the collisión

of the 747s the at

Tenerife

resulted in the recommendation of improved radio Communications, especially in

the take-off phase. On certains airport charts, following a number of other ground incidents, taxiway directions have been printed to help taxying procedures, especially in reduced visibility. The installation of ground radar at

airport

of

Los Rodeos

with a fog risk was recommended and

people in the Tower control speaking a good

English too.

The report atributed

responsability in the following ways:

30 % to the Control Tower (

Spanisg Goverment ) and the remainíng 70 % between the Dutch and American aircrafts, the Dutch company paid more. It was rumoured the the Airtrafic controlers were watching a game of football on Spanish TV and this distracted their attention; needles to say the TV was switched off after the accident.

The most infortunate aspect of

this accident was the analysis published in the

local and Spanish Press. The analysis did not cover

or include a description of the events which

directly led to the tragedy. The only way to have

done this would have been to have waited to see what was recorded in the Blak boxes.

As this tragic accident took

place at

Los

Rodeos

Airport

on the

island

of

Tenerife

, it is a very weak argument to associate the accident

with an incident in other airport on a different

island many hours earlier and even weaker to atribute blame to MPAIAC. Following this line of argument it would be very easy to blame the Dutch and American tourist companies, for having send the tourists to Las

Palmas instead of sending them to Lanzarote or any place on the world. It would

be just as easy to blame the head of the airport authority in

Las Palmas

( who was a military officer ) who should

have sent the planes to Lanzarote instead to

Tenerife

.

This line of arguments is the same as that used to describe the Butterfly Effect, where a butterfly flapping its wings in

Tokio, can cause a hurricane in

Florida

. You will never reach any clear conclusion using this kind of analysis. The

truth is that the misunderstanding between the control tower and the two aircraft was a

result of the fact that radio contact was taking

place between the control tower and two aircraft at

the same time and using the same

frequencies when they should have been using

differents frequencies for each aircraft, " the

collision resulted in the reconnendation of

improved radio communications especially in the

take-off phase ".

xxx

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Airline Pilot's Association ( ALPA ), Accident Report, 1978.

Spanish " Subsecretaría de Aviación Civil "

Accident Report, 1978 (

CAO CIRCULAR AN-/

56)

Madrid

.

Air Disasters

Dialogue from the Black Box.

Stanley Stewart, 1986

*

* *

Aunque lo pareciera, el domingo del día 27 de marzo de 1977 no terminaría

para Juan Velarde como otro día festivo cualquiera. A las 17:06 horas GMT,

momento en que disfrutaba con su familia en las afueras de Madrid de su merecido

descanso, este piloto de Iberia (en la actualidad de 71 años y jubilado, aunque

sigue volando aparatos de época junto a su hijo, de idéntica profesión) no

podía imaginar que a la llegada a su domicilio un mensaje reclamaba su

presencia porque se había producido el que hasta la actualidad (da gracias a

Dios de que así sea) ha sido el accidente aéreo con mayor número de víctimas

mortales: el registrado en Los Rodeos, en el que perecieron 583 personas por la

colisión de dos Boeing 747, uno de la compañía holandesa KLM y otro de la

americana Pan Am.

Aunque lo pareciera, el domingo del día 27 de marzo de 1977 no terminaría

para Juan Velarde como otro día festivo cualquiera. A las 17:06 horas GMT,

momento en que disfrutaba con su familia en las afueras de Madrid de su merecido

descanso, este piloto de Iberia (en la actualidad de 71 años y jubilado, aunque

sigue volando aparatos de época junto a su hijo, de idéntica profesión) no

podía imaginar que a la llegada a su domicilio un mensaje reclamaba su

presencia porque se había producido el que hasta la actualidad (da gracias a

Dios de que así sea) ha sido el accidente aéreo con mayor número de víctimas

mortales: el registrado en Los Rodeos, en el que perecieron 583 personas por la

colisión de dos Boeing 747, uno de la compañía holandesa KLM y otro de la

americana Pan Am.